Kleinhans Music Hall: A Vintage Masterpiece

By Edward Yadzinski

“A concert auditorium is a musical instrument.”

Eliel Saarinen, architect

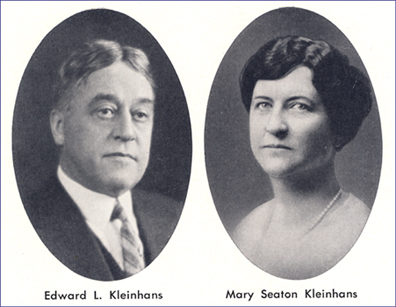

Kleinhans Music Hall is a marvelous token of generosity from Edward L. Kleinhans and his wife, Mary Seaton Kleinhans. The couple passed away within months of each other in 1934. Their entire estate had been designated for the construction and maintenance of an urgently needed concert hall in Western New York – in the words of Edward L. and Mary Seaton – “for the use, enjoyment, and benefit of the people of the City of Buffalo.” For the initial construction, the Kleinhans estate provided $751,704, which was supplemented by a grant from the federal government in the amount of $583,675. The public funds were provided by the Public Works Administration (PWA), of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. The entire management of expenditures and construction was heroically directed by The Buffalo Foundation, all under the devoted stewardship of Edward H. Letchworth (see Before the Music).

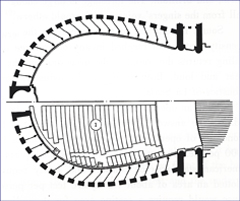

Conceived and designed in 1937-38 by Eliel Saarinen and his son, Eero, Kleinhans’ graceful and sweeping curves remain unique among the great concert auditoriums of the world. Without the statuary and ornate decors of the traditional European concert halls and opera houses, Kleinhans retains a decidedly modern look and feel. The elegant refinement of the hall’s internal dimensions is often remarked, as the expansive curves embrace a large, fully suspended balcony.

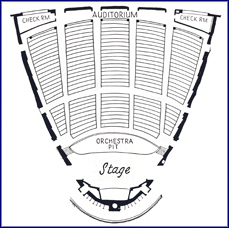

Of particular importance is the overall form of Kleinhans, emulating the fan-shaped proportions of amphitheaters from Greek and Roman antiquity. We should note that there are just three other general shapes in which most concert halls and theaters have been built: the ‘shoe box’ (rectangular style), the ‘oatmeal box’ or ‘coffee can’ (cylindrical style, with a horseshoe hoof print), and the “theater-in-the-round” design (often described as the ‘vineyard style’).

Examples of the ‘shoe box’ style include Boston’s Symphony Hall and Vienna’s Musikverein. The ‘oatmeal box’ style is found in many opera houses, like La Scala in Milan, but also in concert halls, the most famous of which is Carnegie Hall in New York City. We should note that Saarinen displayed both savvy and courage in his choice to go with the ‘fan shape’ of the main auditorium in Kleinhans Music Hall. For one, there was not a single celebrated example of the fan-shape design in use at a major concert venue anywhere in the world. By contrast, examples of successful ‘shoe box’ or ‘coffee can’ designs could be found in many cities in Europe and the United States.

During the later decades of the 20th century, the ‘theater-in-the-round’, or ‘vineyard’, style emerged from a far-distant past into the form of a mature concert hall. Today it is the preferred style for most major concert venues around the world.

Beyond the selection of a fan-like design, it was yet another leap of faith when Saarinen decided to integrate the curved proportions of a violin into his architectural plans for Kleinhans. (Saarinen revealed his idea in an essay he later wrote on the construction of the hall.)

In sum, Saarinen’s choices were not only adventurous but risky, in that concert hall design has always been a paradoxical science. Although the fundamentals of auditorium acoustics have been understood for centuries, getting the parameters ‘just right’ remains a game of chance – not quite a roll of the dice, but close. The saga of the acoustical agonies at New York’s Lincoln Center is a classic example. The main concert hall at the Center has been rebuilt five times, all in a quest for the revered ‘Sonic Grail’ of Carnegie Hall just blocks away. Although fortuitous in part, Saarinen’s gambit to blend antiquity with the lyrical curves of the violin brought a splendid result.

Overall, the parameters of concert hall design must meet practical needs like seating capacity, stage function (concert hall, opera or ballet theater, general use) and structure style (fan shape, shoe box, etc.). The difficulty arises when dimensions are defined and materials selected – even the fabric covers for the seats can be critical. The brief discussion below offers a summary of the issues by highlighting the acoustical DNA of Kleinhans.

The metaphor of a ‘vintage music hall’ might best describe the very real science behind Kleinhans’ phenomenal acoustics. For example, when musicians describe the sound of a particular concert hall, a curious jargon emerges as if the subject were about wine: body, richness, color, bouquet, lively, sweet, dry, robust, mellow, and so on. We cannot resist telling the story of the 1778 completion of La Scala in Milan, after which workers believed that the broken wine bottles they’d mixed into the concrete gave the great opera house its warm and mellow sound (the workers always brought wine to have with lunch).

To achieve the desired tonal ambiance or flavor of a concert hall, designers have to deeply consider three elements of sound propagation:

1. Reverberation – measured in seconds

2. Reflection and Diffusion – uniformity of sound throughout an auditorium

3. Absorption – how well sound maintains with or without an audience

By convenient analogy, wine makers are likewise concerned with three natural elements as they hope for a ‘vintage’ year: sunshine, rain and temperature. And whether the objective is a vintage harvest or a vintage hall, the issues of time and timing are everything. In both instances, what happens exactly when yields the final result.

A simple demonstration speaks volumes about Kleinhans’ superb acoustics: take a seat in the far-upper last row in the balcony, 145 feet from center stage. Have someone in the middle of the stage whisper ‘Can you hear me now?’ The result is amazing – the whisper fills your balcony ear as if secretly amplified. Kleinhans enables the delicate sibilants and subtle timbres of the phrase to be heard without picking up spurious resonances as it travels through the hall.

Likewise, at the deep end of the sound spectrum, if a solitary low E on a string bass on stage is played with a quiescent pizzicato (plucking the string), again your balcony ear – half a football field away – will be treated to a sustained, low E for several seconds as Kleinhans shows off its acoustic depth.

While Kleinhans easily handles the big moments from symphonic barn-burners like Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture, the ‘whisper demonstration’ reveals why the hall is superb for listening to delicate offerings like Baroque concertos or exquisite arias from the world of opera. En garde: although the hall is a lyrical showcase in its own right, Kleinhans’ acoustical efficiency makes it dangerously easy for an orchestra to overpower a soloist. Alas, we are reminded of Lukas Foss’ cryptic remark: “Show me dangerous music.”

An important element in concert hall sound propagation is called ‘diffusion’ – a measure of how well sound is carried uniformly throughout the hall. If diffusion is just average, an otherwise good sounding hall will have ‘dead spots.’ Very closely related to diffusion is the phenomenon of ‘reflection.’ In general, 90% of the sound we hear in a good concert hall has been recycled (reflected) from the walls, floor, and ceiling. If the surface walls are too reflective (not enough absorption), a concert hall can begin to sound like a glass and hardwood gymnasium. The walls of concert halls must never be parallel (nor should the ceiling and floor) because sound tends to get trapped, bouncing back and forth in strange tempos and accents of its own. However, some great concert halls like Vienna’s Musikverein, do have parallel walls, although the flat surfaces are broken up with Romanesque windows, statuary, large chandeliers, sloped balconies, etc.

Another critical factor is known as ‘absorption’ – a measure of how long a sound will persist in a concert hall before it dies away. Absorption is linked to the measurement known as reverberation time. Kleinhans has a relatively short reverb time, sometimes described as ‘dry’ – like a fine claret from Bordeaux or Burgundy. By comparison, a hall that has a relatively long reverb time, like the Musikverein in Vienna, is sometimes described as ‘mellow’ or ‘robust.’ Again, the wine analogy fits. But of course, it is possible for a hall to be too dry (dead) or too resonant (boomy).

Less obvious is the issue of seat design – each seat should absorb as much sound when it is empty as it does with an occupant. To achieve this, the cushions and fabric coverings are carefully selected and tested. Finally, the issue of size: with 2,839 seats (main floor – 1,575, balcony – 1,264), Kleinhans ranks among the largest concert halls in the world. By comparison, Cleveland’s Severance Hall seats 1,890 while Vienna’s Musikverein accommodates just 1,680.

Given all of the above, we gain respect for the artistic balance and practicality of Kleinhans – a veritable shrine for music and a vintage hall, par excellence.

*Photos of Saarinens and KMH mezzanine courtesy of the Burchfield Penney Art Center